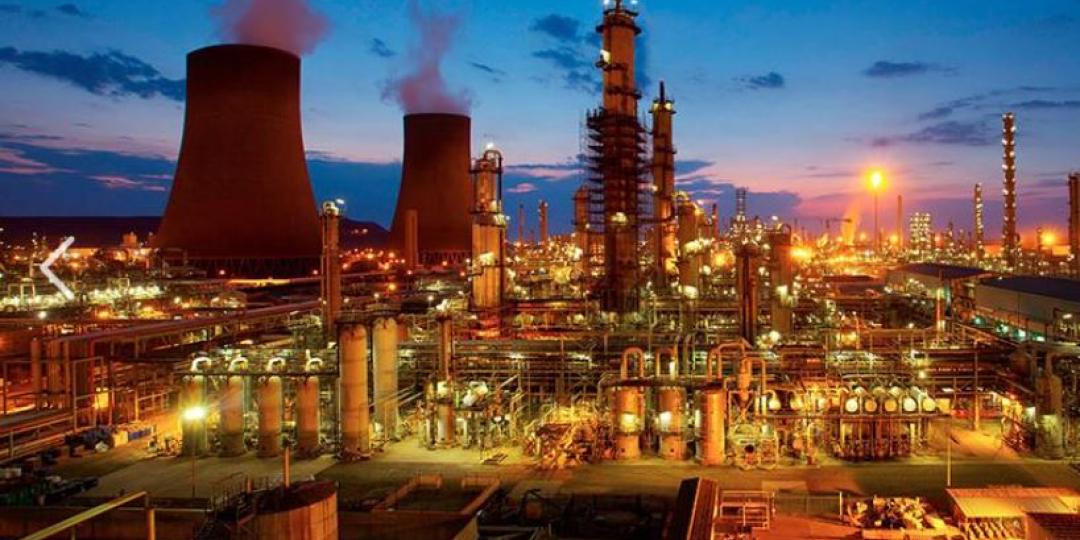

Existing infrastructure at the Port of Richards Bay as opposed to new infrastructure proposed for the Port of Ngqura and the Coega Industrial Development Zone could help South Africa avoid a gas supply cliff.

According to James Mackay, PwC director for capital projects and infrastructure, South Africa’s gas feed from Mozambique, our primary supplier, is steadily dwindling and unless urgent measures are instituted to avoid a shortfall, it could have a significant impact on local industry by 2023.

Speaking at the release of PwC’s “Africa oil and gas review 2019”, Mackay indicated that the government’s intention to develop an import terminal for liquid natural gas (LNG) at Coega could significantly add to infrastructural implementation expenses and logistical complexity around addressing South Africa’s gas needs.

In comparison, he argued that Richards Bay was a far more cost-effective option for the construction of such a terminal as it already had the land-side infrastructure in place and was much closer to Gauteng where there was the largest industrial need for gas.

Mackay’s views come amid warning signs that Sasol’s fuel, power and chemical production plants in Secunda and Sasolburg could be adversely affected in the next five years unless urgent action is taken.

Moreover, Mackay stressed that the right action and strategy was crucial as the time it would take to implement the necessary measures already appeared to be insufficient for the time it might take to remedy the situation.

Apart from the effect a gas cliff could have on Sasol, which receives its gas from a pipeline in the Inhassoro region in Mozambique, Mackay warned that downstream industries employing around 45 000 people and contributing about R150 billion annually to the economy, could be in jeopardy.

Companies that could be left stranded unless their near to longer-term gas future was secured, included Columbus Stainless, Consol Glass, Hulamin and Nampak, Mackay said.

And although South Africa is right next to Mozambique where at least $54 billion has already been spent on developing LNG facilities up north, gas from the Rovuma Basin south of the Tanzanian border will only come on line in about 10 years.

South Africa’s gas condensate finds earlier this year at the Brulpadda resource south of Mossel Bay will also take at least a decade before they are expected to start providing supply relief.

The fact that the government’s Integrated Resource Plan is not really making provision for a gas-to-power programme beyond 2030 is also said to contribute to industrial uncertainties about what government intends to do to secure the country’s gas supply future.

And as gas supply from Mozambique is expected to amount to annual shortfalls of 98 million gigajoules by 2025, far below what is required for the country’s grand-scale consumption, South Africa needs a consolidated public-private plan to avoid a gas cliff.

It entailed, among other crucial decisions, consensus about using Richards Bay as a preferred LNG entry point, Mackay stressed.

“But at the moment, there is no policy certainty with regards to who will do it, how it will be done and which port will be prioritised,” he told a fellow trade publication.