The issue of rising detention charges is in the spotlight once again, with maritime consultancy Sea-Intelligence analysis revealing that they are definitely on the rise.

These daily charges, to be paid by cargo owners for use of the shipping lines’ empty containers outside of the terminal or depot, are highly relevant given the current equipment shortage crisis, says the consultancy’s CEO Alan Murphy. “Tightening detention rules would incentivise cargo owners to return their equipment faster, in turn helping to resolve equipment shortages.”

Unfortunately, says Murphy, shipping lines do not provide consistent data across the industry, and in some cases the data is very country- and carrier-specific. Given the quality and consistency of their publicly available data, Sea-Intelligence has used data published by Hapag-Lloyd for the analysis. “This should not in any way be construed as the German carrier being “better” or “worse” than any other carrier, but simply reflects the availability of good, long-term data from Hapag-Lloyd,” Murphy adds.

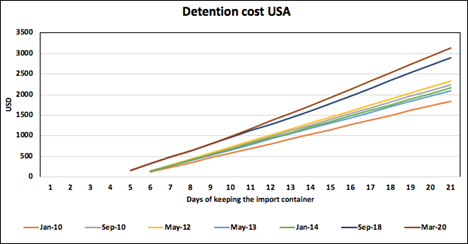

Figure 1 shows the detention costs for a US importer, based on the time it takes to redeliver the empty container to a depot. It can be seen that the detention charges have grown over the years, as the slopes of the curves increase over time. Furthermore, there is a shift in 2018, where the amount of free time is reduced from five to four days. “However, the latest increase came into effect in March 2020, so it cannot be seen as a consequence of the current equipment shortage crisis.”

For Germany and the UK, the recent container shortage challenges did not give rise to changes in the standard detention rules, not even Brexit in the case of the UK, Murphy points out. “In Turkey, a recent announcement in April changed the detention rules, with no change to detention being paid if the container was returned within 10 days, but a sharp increase when this was exceeded. A similar development was seen in Spain, with no change if the container is returned within 20 days, and a 20% increase if this period is exceeded.”

Murphy points out that for the sample of countries included here, there is no indication that the pandemic and the associated bottleneck problems have led to a systematic increase in the detention charges. “Some countries have indeed seen recent sharp increases, but others have seen no increases. There is no pattern to be seen. It is equally clear that the development is purely locally driven, even to the point of how the days and charges defined differ by country.”

It’s an issue that was covered by Freight News in December last year when the International Federation of Freight Forwarders Associations (Fiata) and The South African Association of Freight Forwarders (Saaff) called on the South African government to support key considerations laid out by the US Federal Maritime Commission (FMC) in its “Final Rule on Demurrage and Detention (D&D) to assess the reasonableness of these practices”.

According to the Saaff statement, the FMC’s decision, which came after six years of investigation with all actors in the supply chain, concluded the likeliness of a long history of unjust and unfair D&D practices.

“Whilst there are country- and port-related variances, the FMC findings apply globally as demurrage and detention is a common and widespread topic of contention,” the statement said.

“If the FMC has identified demurrage and detention practices that are likely to be considered as unjust for the USA, these practices are also unjust and unreasonable for the rest of the world.

“Governments must therefore have greater scrutiny over demurrage and detention practices to ensure that they are considerate and reasonable for the good of their own economies.”