The Lobito Corridor on several occasions has been described as a ‘game changer’ by freight stakeholders such as Duncan Bonnett, director of Market Access and Research at Africa house, and Mike Fitzmaurice, chief executive of the Transit Assistance Bureau.

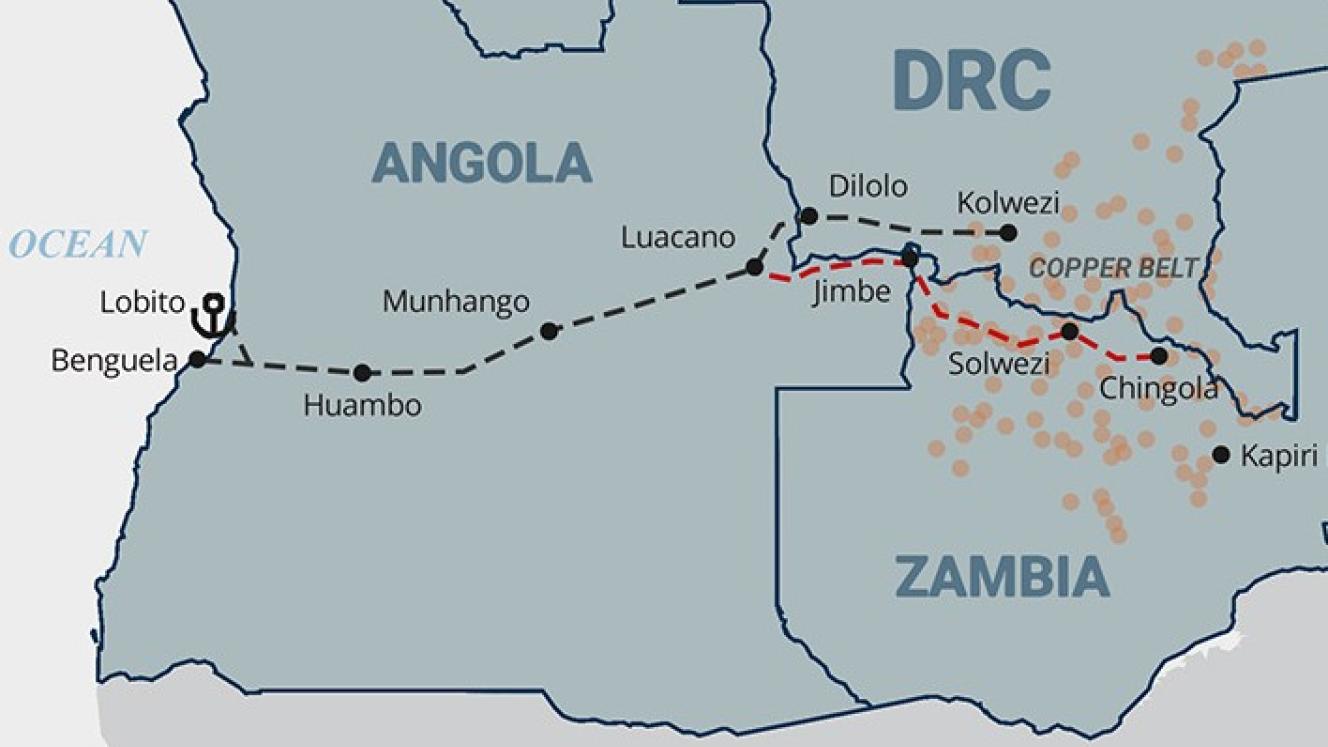

But the bulk rail link connecting the Copperbelt in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Zambia with Angola’s southernmost port, matters for another reason, say Shirley Webber and Stephen Seaka of Absa’s Corporate and Investment Banking (CIB) division.

According to Absa CIB’s managing principal and coverage head of Resources and Energy, and managing executive for Public Sector and Growth Capital Solutions respectively, the corridor forces a more fundamental question on to the table: if the next generation of global industry is going to draw on Africa’s critical minerals, what scale of planning can genuinely support that opportunity?

“In practice, the geology is regional, but industrial policy is still national. Lobito exposes that mismatch and demonstrates how coordinated corridors can begin to bridge it,” Webber and Seaka write in an article titled How Africa Can Turn Fragmented Mineral Belts into Coherent Regional Value Chains.

“Africa holds close to a third of the world’s known reserves of future-facing minerals. These include the metals driving the global energy transition – copper, cobalt, manganese, graphite, nickel, lithium and the platinum group metals.”

A broader suite of inputs used in advanced manufacturing and emerging digital technologies include from rare earth elements to titanium and vanadium, the authors say.

The challenge is that these minerals are dispersed across the continent – copper and cobalt across the Central African Copperbelt; lithium, nickel and graphite across Southern Africa; manganese and platinum group minerals across South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe; bauxite is concentrated in Guinea; and rare earth prospects are emerging through Namibia and parts of East Africa.

Currently, the International Energy Agency projects higher demand for key battery metals and transition-linked commodities over the next two to three decades.

As such, “Africa’s mineral endowment places it at the centre of an emerging geopolitical and industrial reordering,” Webber and Seaka argue.

“This makes the case for regional thinking almost self-evident.

“But many continental strategies blur the distinction between regional cooperation and regional approaches to beneficiation. Regional cooperation is about how states organise the rules of the game across borders. It includes tariff alignment, customs procedures, rail and port concessions, environmental and social standards, power-pool governance, dispute-resolution mechanisms and the regulatory treatment of long-term public-private partnerships.

“Regional beneficiation, by contrast, is about where along the value chain different activities sit and how those activities are sequenced. Ore can be crushed, concentrated, smelted, refined, turned into precursors, assembled into components and eventually integrated into finished products.

“Some of these steps require substantial power and water; some are knowledge-intensive; some are highly trade-exposed and shaped by logistics costs. It seldom makes sense to duplicate each step in every country that hosts a deposit. It is more efficient to map which segments of a copper-cobalt-manganese-lithium chain should sit in which locations along a corridor, then design fiscal regimes, power investments, and skills programmes accordingly.”

Webber and Seaka emphasise that the continental policy landscape is beginning to move in this direction.

They write that the African Union’s Green Minerals Strategy positions critical minerals as a regional industrialisation opportunity and promotes integrated value chains and corridor-based infrastructure planning.

Regional economic communities that provide sub-continental platforms in support of coordination include the Southern African Development Community, the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, and the Economic Community of Central African States.

Webber and Seaka say that although the mining and industrial frameworks of these blocs are uneven, “they offer the institutional footing on which more deliberate regional planning can be built”.

However, turning these frameworks into functioning corridors requires a different discipline from governments.

“It means treating a corridor as a single planning unit for power, water, data connectivity and skills, even while it traverses several jurisdictions. It means aligning fiscal terms enough to prevent destructive competition for smelters and refineries, while allowing differentiated incentives where countries have distinct industrial strengths. It also demands joint approaches to environmental and social governance, so that high standards become a feature of the corridor rather than a source of regulatory arbitrage. These elements form the operational foundation on which regional value-chain design can take shape.”

The key to unlocking success through corridor collaboration, the authors stress, is the private sector, situated as it is at the centre of industrial growth requirements.

“Mining companies and their supply chains will not commit to multi-decade smelting or refining investments unless they see predictable corridor-wide frameworks on transport, power pricing, fiscal regimes and environmental standards.

“Battery and electronic vehicle manufacturers will only treat African corridors as strategic production nodes if they can access sufficient scale, consistent quality and credible delivery timelines. Regional banks and development finance institutions will structure project finance and corporate facilities more confidently when risk is shared across a corridor with pooled revenue streams rather than being tied to the fiscal position of a single sovereign.”

Webber and Seaka end their article on a very strong point, cautioning that Africa does not have the luxury of treating regional cooperation and regional beneficiation as afterthoughts.

“If the continent continues to negotiate in small, fragmented units, the result will be a patchwork of export restrictions and incentive schemes that strain investor confidence without building the connective tissue of shared infrastructure and industrial capacity.

“If, instead, leaders use projects such as the Lobito Corridor as prototypes for how to align geology, logistics and industrial policy at a regional scale, the continent can begin to shape global value chains rather than simply feeding into them.”