Lesotho has now secured official access to Starlink, having granted a 10-year operating licence to the service in April 2025.

In practical terms, this means that a country effectively landlocked by South Africa will soon enjoy faster, cheaper, low-latency internet connectivity than its much larger neighbour.

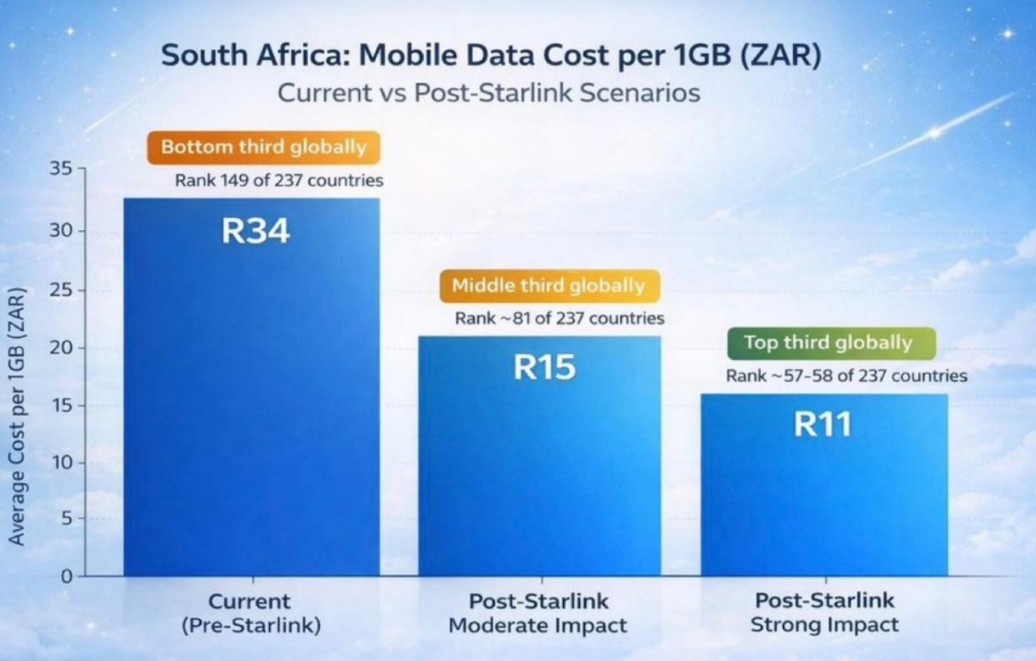

The attached chart (see below), built off AG Capital’s baseline projections, highlights just how binding the constraint of data costs has become. South Africa currently sits in the bottom third globally for mobile data affordability, with an average cost of roughly R34 per 1GB.

In many cases, the cost of 1GB exceeds the hourly minimum wage rate. Under even a moderate competitive shock (such as the entry of low-cost satellite broadband) our projections suggest prices could halve, lifting South Africa into the middle of the global rankings.

A stronger competitive impulse would push costs closer to R11 per GB, placing the country firmly in the top third globally. This is not a ‘tech policy’ debate. It is a growth debate.

Affordable, high-bandwidth internet is one of the most powerful poverty-reduction tools available. It collapses the distance between informal and formal markets, between rural communities and global demand, between under-resourced schools and world-class educational material.

With connectivity, households can learn, trade, freelance, code, consult, and sell – often without leaving their communities. The opportunity cost becomes even starker when digital access is combined with modern AI tools.

Open access to information platforms, AI-driven education, and automated public-finance auditing tools would materially change how citizens engage with the state. Even a conservative improvement in fiscal efficiency from, say, 50% of public spending reaching productive use to 75%, would feel equivalent to a massive increase in infrastructure and social investment, without raising a cent in additional tax revenue.

South Africa’s resistance to Starlink is therefore not about regulation, but rather foregone growth. While Lesotho accelerates connectivity across difficult terrain, South Africa continues to defend an expensive, exclusionary status quo. In a world where data is capital and connectivity is infrastructure, blocking access is not neutrality. It is an active drag on economic progress.

Progress is not something governments get to veto. While much of the world is rolling out Starlink, South Africa remains trapped in licensing theatre. We protect incumbents, invent ownership gymnastics, and call it policy – trading long-term growth for a handful of short-term concessions. If this is our digital strategy, the divide will not narrow; it will widen.

As always, the costs will be borne not by policymakers or protected interests, but by the millions of ordinary South Africans already excluded from opportunity.