The global economy’s “speed limit”— the maximum long-term rate at which it can grow without sparking inflation —is set to slump to a three-decade low by 2030.

This is according to a new World Bank report which calls for an ambitious policy push to boost productivity and labour supply, ramp up investment and trade, and harness the potential of the services sector.

The report, Falling Long-Term Growth Prospects: Trends, Expectations, and Policies, offers the first comprehensive assessment of long-term potential output growth rates in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

It documents a worrisome trend: nearly all the economic forces that have powered progress and prosperity over the last three decades are fading.

As a result, between 2022 and 2030 average global potential GDP growth is expected to decline by roughly a third from the rate that prevailed in the first decade of this century — to 2.2% a year. For developing economies, the decline will be equally steep: from 6% a year between 2000 and 2010 to 4% a year over the remainder of this decade. These declines could be much steeper in the event of a global financial crisis or a recession.

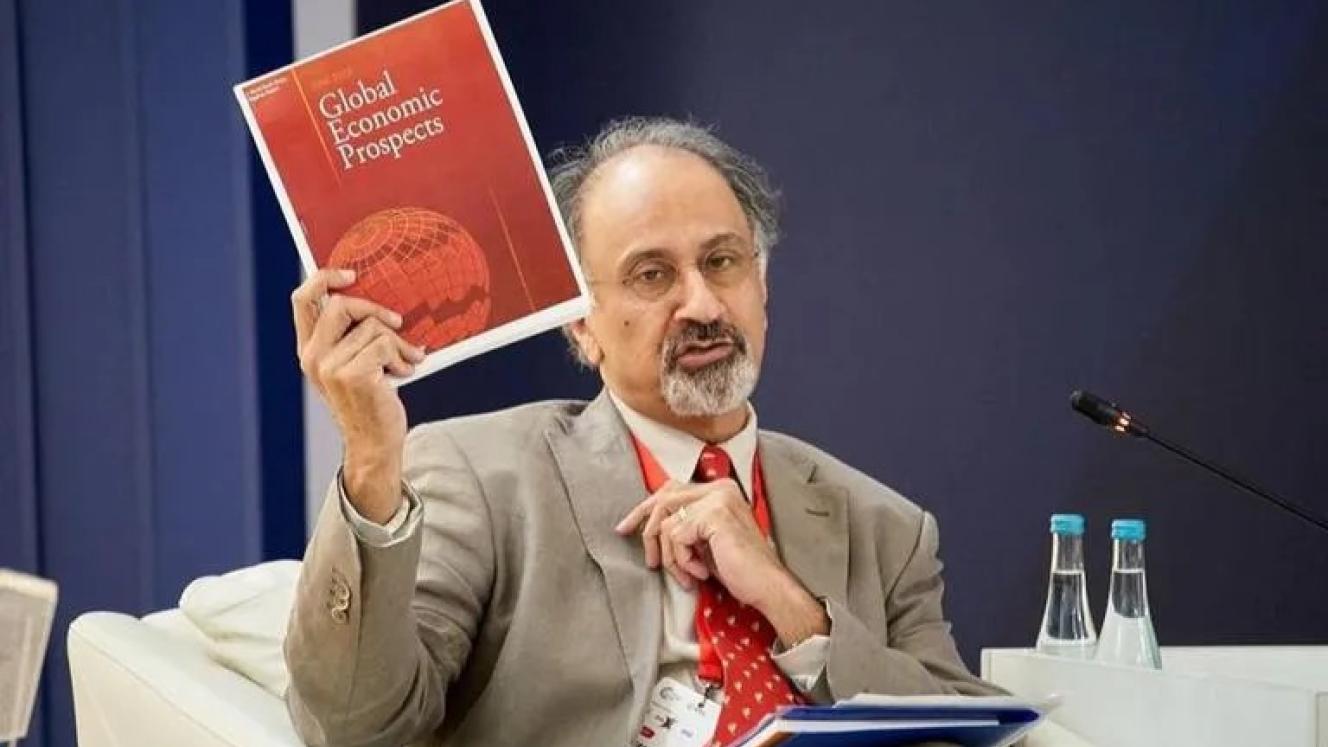

“A lost decade could be in the making for the global economy,” Indermit Gill, World Bank chief economist and senior vice president for development economics, said.

“The ongoing decline in potential growth has serious implications for the world’s ability to tackle the expanding array of challenges unique to our times — stubborn poverty, diverging incomes, and climate change. But this decline is reversible. The global economy’s speed limit can be raised, through policies that incentivise work, increase productivity, and accelerate investment,” Gill said.

The analysis shows that potential GDP growth can be boosted by as much as 0.7% to an annual average rate of 2.9%, if countries adopt sustainable, growth-oriented policies.

“At the national level, each developing economy will need to repeat its best 10-year record across a range of policies. At the international level, the policy response requires stronger global cooperation and a re-energised push to mobilise private capital,” Ayhan Kose, a lead author of the report and director of the World Bank’s Prospects Group said.

The report lays out achievable policy options. It introduces the world’s first comprehensive public database of multiple measures of potential GDP growth, covering 173 economies from 1981 to 2021. It is also the first to assess how a range of short-term economic disruptions, such as recessions and systemic banking crises, reduce potential growth over the medium term.

“Recessions tend to lower potential growth. Systemic banking crises do greater immediate harm than recessions, but their impact tends to ease over time,” Franziska Ohnsorge, a lead author of the report and manager of the World Bank’s Prospects Group said.

The report highlights national-level policy actions to promote long-term growth prospects, including the alignment of monetary, fiscal, and financial frameworks, and robust macroeconomic and financial policy frameworks. It called for policy-makers to prioritise taming inflation, ensure financial-sector stability, reduce debt, and restore fiscal prudence to attract investment.

Investment in transport and energy was key, especially in climate-smart agriculture and manufacturing, and land and water systems to strengthen resilience against natural disasters.

Trade costs, mostly associated with shipping, logistics, and regulation, effectively double the cost of internationally traded goods. The report advised that countries with the highest shipping and logistics costs could cut their trade costs in half by adopting trade facilitation and other practices of countries with the lowest shipping and logistics costs.

The services sector could become the new engine of economic growth. Exports of digitally delivered professional services related to information and communications technology climbed to more than 50% of total services exports in 2021, up from 40%in 2019 the report found. The shift could generate vital productivity gains if it results in better delivery of services.

About half the expected slowdown in potential GDP growth to 2030 will be attributable to changing demographics, including a shrinking working-age population and declining labour force participation as societies age, the report found. Boosting labour force participation rates could increase global potential growth rates by as much as 0.2% a year by 2030.